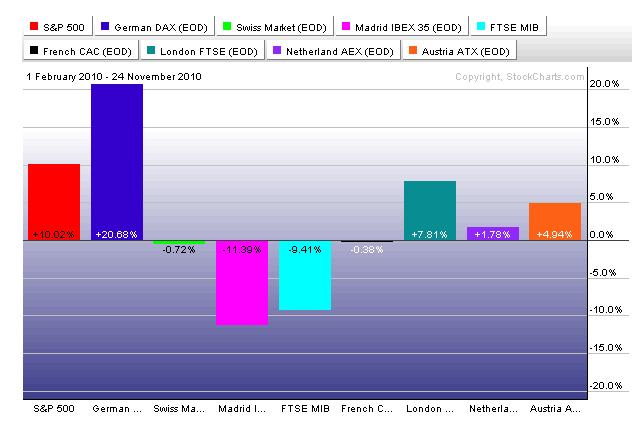

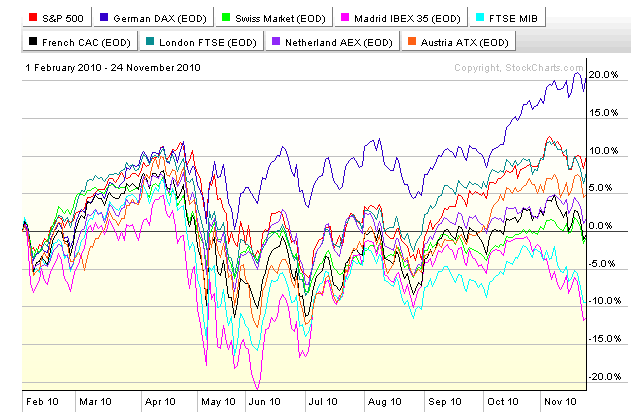

Performance of international stock market indices in local currencies. Source: StockCharts.com

Looking at the performance of international stock markets over the last 200 days, the German Dax index stands out. But why?

Sure, Germany is an island of prosperity amongst the European turmoil. Low unemployment, strong economic growth and a stable political system help.

You could argue if it makes sense to distinguish between Deutsche Telekom and Telefonica on the basis of where they are headquartered. But aren’t the largest companies (hence those included in stock indices) serving similar customers in similar regions? Isn’t Volkswagen selling more cars in China than in Germany anyway? 50% of BMW’s growth contribution from China?

Or are equity investors following bond investors in a flight from the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Spain)? For bond holders, a break-up of the Euro zone would be dramatic, as issuers will either force conversion into (new) local currencies (leading to currency losses) or find themselves unable to service Euro debt and default (leading to haircuts on principle).

But equities? Imagine what a break-up of the Euro would do to German exports to those countries. Stock markets in weak currency regimes are usually, at least in local terms, appreciating. But for German stocks this would be a negative.

If weak countries leave the currency zone, the Euro could actually re-strengthen (or, if Germany decides to quit, a strong New Deutschmark would have the same effect on German exports).

Performance of international stock market indices in local currencies. Source: StockCharts.com

Performance of international stock market indices in local currencies. Source: StockCharts.com

Looking at the under-performance of Spanish and Italian stocks leads to another explanation: international investors are withdrawing from countries in danger of being future candidates for bail-outs (with the usual prescription of spending cuts and tax hikes that could damage local net profits and/or lead to political instability).

However, once Spain tumbles, the costs of bail-outs will become astronomical and overwhelm the cohesion of the Euro-zone. Things will get out of control quickly if only for the unavoidable bank runs (depositors in weak countries withdrawing their Euro deposits before a mandatory exchange into a new currency). Government “guarantees” of deposits will become worthless once the government is bankrupt, too (as seen in Ireland).

Equity investors have an admirable lightheartedness amidst an outlook which can only be described as dire. Do they understand they are the last asset class to get paid back? When a company cannot pay back its debt, the equity is usually worthless. The same applies on a national level. Before a country goes bankrupt, it will apprehend all available profits (if any) and funds at companies in its jurisdiction. Surely some profits can be stashed away at foreign subsidies, but which investors will rely on those when pictures of rioting masses are dominating the headlines?