While Greece is pretty forthcoming with its apocalyptic fiscal data, the same cannot be said of Portugal.

When it comes to inquiring about monthly fiscal deficits you bite on granite. Banco de Portugal has limited quarterly figures. The “Instituto Nacional de Estatistica” has conducted a study about population growth in Angola. It supplies data series on important topics as the “self-sufficiency ratio of wine”, the “movement of passengers on inland waterways”, and, not to be missed, the “crude divorce rate”.

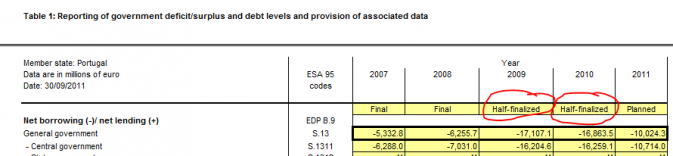

Impossible to find a simple table about the general government fiscal deficit, preferably by month. Maybe I was looking for something that does not exist. Maybe I am too impatient; after all, the numbers for 2009 and 2010 seem to be only “half-finalized”:

Souce: EDP (Excessive Debt Procedure) tables, Eurostat, October 2011

Souce: EDP (Excessive Debt Procedure) tables, Eurostat, October 2011

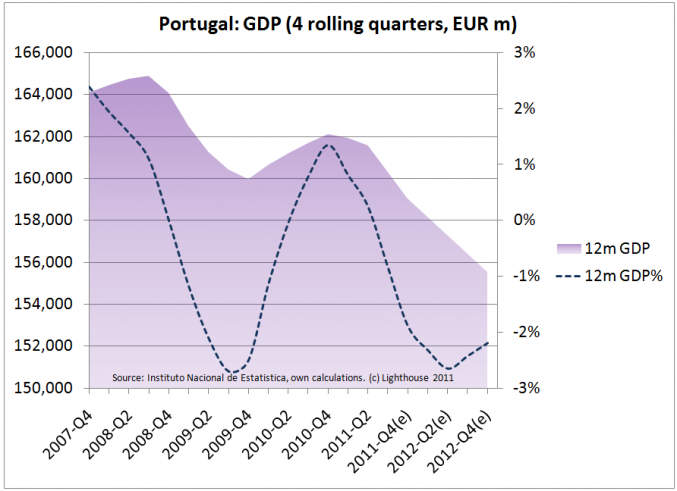

Let’s work with what we have: quarterly GDP numbers and the governments forecast of -2.2% GDP growth in 2011 as well as -1.8% in 2012:

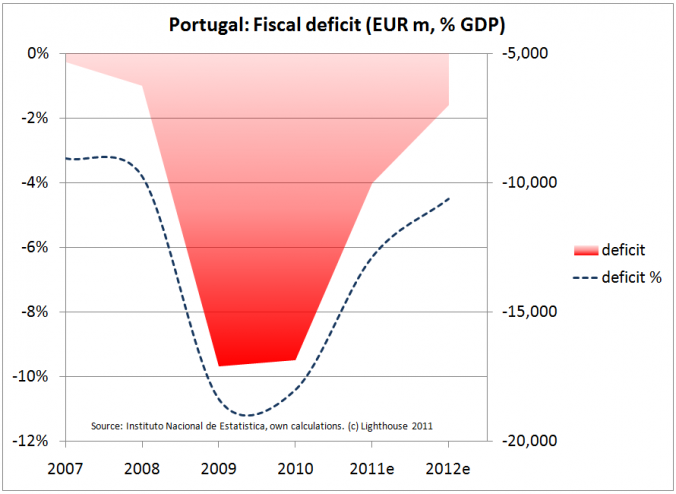

Now on towards the fiscal deficit. 2010 numbers got bumped up a bit from the “Madeira”-effect (discovery of formerly undisclosed debt, a.k.a. the “Greek” maneuver). The deficit is supposed to decline from roughly EUR 17bn (2009 and 2010) to 10bn (2011e) and 7bn (2012e).

In May, shortly before receiving a EUR 78bn bailout, the Portuguese government trumpeted encouraging snippets regarding the state of the economy. “Fiscal revenues up 16.8% y/y in April” (May 20th). “January-through-April central government deficit EUR 1.55bn, 2.28bn less than a year ago” (5/20). The new government announced “to set an example of cutting spending in administration” and intended “to surprise, go beyond bailout terms” (Coelho 6/6).

The good news continued: “Central government deficit for the first five months of 2011 cut to 1.03bn”; “State spending fell 7.2%, revenues rose 6.9% in the period January through May” (June 20th).

With all those feel-good reports it was only fair for the EU’s Troika report on Portugal to be “very positive” (Baroso, June 23rd). The EFSF disbursed its funds to Portugal on June 29th.

However, as anybody who has ever visited a Hungarian coffee house can confirm, as soon as you pay the fiddler, the music stops.

However, as anybody who has ever visited a Hungarian coffee house can confirm, as soon as you pay the fiddler, the music stops.

After six months, “there was a shortfall of 1.1% of GDP in budget” (Finance Minister, August 12th). Wait a minute. According to the INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatistica) the budget deficit for H1 2011 amounted to 8.4% of GDP or roughly EUR 6.7bn. So we went from 1bn at the end of May to 6.7bn mere four weeks later?

Of course, the new government found a “colossal” EUR 2bn hole in the public accounts “left by the outgoing Socialists” (Telegraph, July 18th). From then on, it was only downhill. “The country’s situation is grave” warned the Finance Minister (September 6th). He added “We are facing a serious financial crisis” (September 14th).

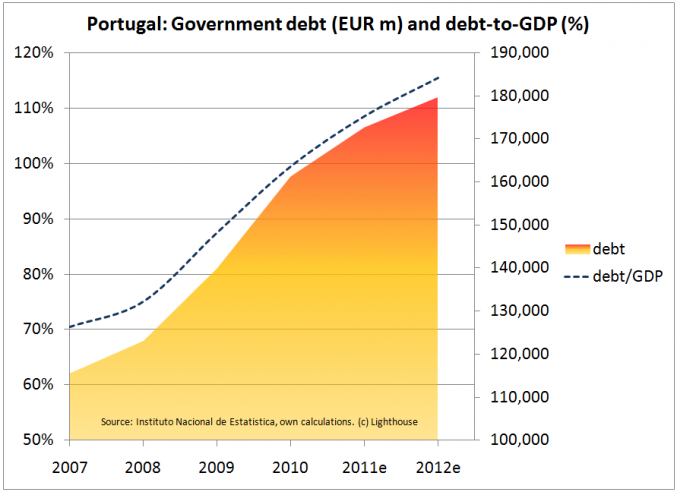

With factory orders declining by 16.8% in August and ECB financing for Portuguese banks rising to EUR 46bn (from 39bn in March) there is really not much to cheer about. How realistic are the governments projections then? How is it possible for debt-to-GDP to peak at 106.8% in 2013 (government, August 31st) when, taking the governments own numbers, one arrives at 115% by 2012?

In view of a rapidly deteriorating situation, is it really necessary to produce (government on 8/31st) wildly unrealistic forecasts such as budget deficits of 1.8% (2014) and 0.5% (2015)?

In view of a rapidly deteriorating situation, is it really necessary to produce (government on 8/31st) wildly unrealistic forecasts such as budget deficits of 1.8% (2014) and 0.5% (2015)?

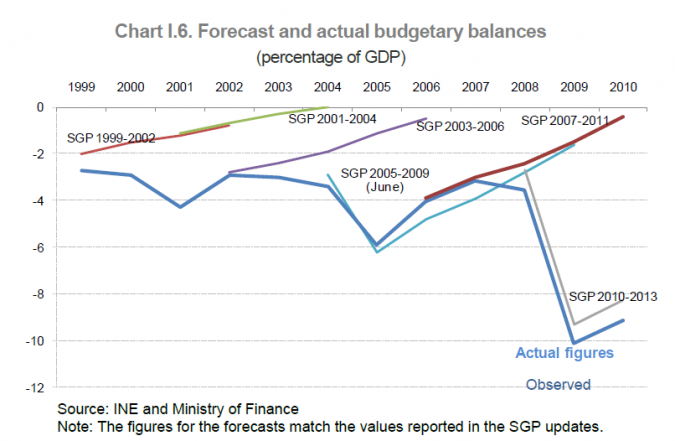

To evaluate past forecasting skills one look at the “SGP” (Stability- and Growth Programme) should suffice:

A case could be made for countries with excess savings to support those who enable those savings via trade deficits. However, a certain accountability and realistic assessment of the situation would be desirable. The “very positive” Troika report seems to have been co-authored by copious amounts of Madeira wine.