Politicians and non-elected maquinistas are still trying to figure out how to make the still-borne EFSF (European Financial Stability Facility) walk, or better, fly. A month after the “miracle of Cannes”, the trumpets of victory over the debt crisis have fallen silent. Instead, the first EFSF bond issue after the G20 summit ended up in disaster (reduced, postponed, not fully placed).

If you thought this experience was a lesson on how not to fight a debt crisis you were wrong: more debt, leveraged via a complicated structure, insured by itself, completely unfunded. Peter Tchir made the effort to go through the “EFSF guidelines”; his verdict: “beyond comical”. I am getting tired of hearing about new “miracle cures” every other day. It is such a waste of time. Like a pal, who, every other weekend, wants to introduce his “new” girlfriend and you wonder if it is worth to be nice and strike up a conversation.

If you thought this experience was a lesson on how not to fight a debt crisis you were wrong: more debt, leveraged via a complicated structure, insured by itself, completely unfunded. Peter Tchir made the effort to go through the “EFSF guidelines”; his verdict: “beyond comical”. I am getting tired of hearing about new “miracle cures” every other day. It is such a waste of time. Like a pal, who, every other weekend, wants to introduce his “new” girlfriend and you wonder if it is worth to be nice and strike up a conversation.

The house is on fire, but politicians are discussing if buying a second dog would make the property safer, and what kind of collar it could possibly wear.

Should we believe ECB’s Noyer when he says (11/28) “The economic situation in Italy is not that bad”? Why then, may one ask, did Italy prefer not to release its Q3 GDP data (was scheduled for 11/16)? Is the third-largest government bond market on earth wrong in yielding 7-8% across the curve?

No, it is “not that bad”. It is horrible.

Take the rumor about EUR 400-600bn IMF help for Italy (strategically leaked on a Sunday). What does it say about Europe if the IMF has to bend over backwards to bail out one country for 12-18 months?

It says: “Europe is bankrupt and cannot save itself”.

Remember the latest product innovation from the IMF, announced not even a week ago? “Credit lines” of 500% of a country’s quota. Spain and Italy would be able to receive $30-60bn – a joke in the big scheme of things.

The program was already obsolete a few days after its inception. This is how fast the fire is burning through the attic – and the owners are still sleeping.

If the EUR 600bn for Italy materialized, Spain would feel entitled to some help, too. But Italy has first-mover advantage. Hence the ominous warning from the incoming Spanish government to “mull financial options without ruling out an application for international aid” (11/22).

Once Italy and Spain fed at the trough, it will be empty. The poor Portuguese will be left behind, as it will be every man for himself.

Greece has been reduced to a mere side-show. The only question being if the next tranche (EUR 8bn) will be paid out before Greece declares a “temporarily suspended debt service” on December 16 as EUR 12bn of debt matures. Even assuming the EU/IMF help flows, the cash drain, together with a monthly fiscal deficit of 1bn+, would be 5bn.

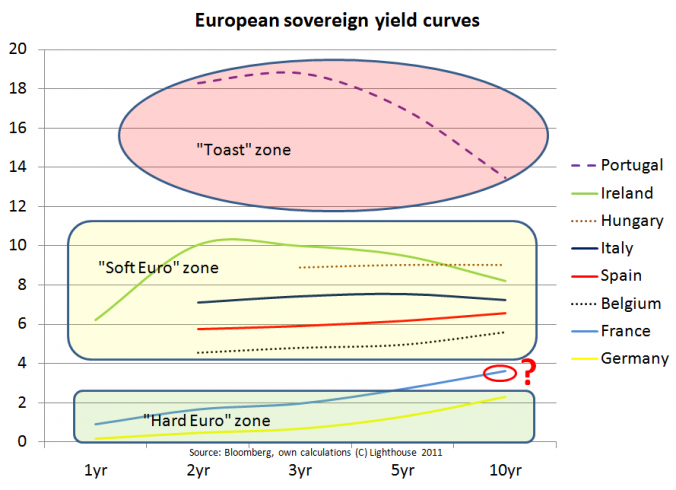

As usual, the bond market has already an idea on how this will pan out. Looking at various yield curves we get the following picture:

- Greece is “off the chart” (in the “toast” zone)

- Portugal will not make it as debt and interest is not sustainable and the EFSF struggles to raise bailout funds.

- The “soft Euro-zone” could survive by aggressive monetization of debt by the ECB – once the German hardliners quit. Inflation would probably follow in a few years, but that is another question.

- The “hard Euro-zone” would consist of Germany and the Netherlands. They unilaterally quit the Euro-zone and introduce a pegged currency pair.

- France is really the only unsolved question in this puzzle. Bond yields have peeled away from Germany a bit too far. Historically, France was a “soft” currency country with frequent realignments of exchange rate under the European ERM (Exchange Rate Mechanism). Given the strong political ties France will probably be forced to stay married to Germany, but it will be an unhappy marriage, with an eventual break-up at a later date.

- I have included Hungary just out of curiosity, since their love-hate relationship with the IMF is slightly entertaining.

Sometimes I get the impression Germany’s insistence on austerity is in fact an attempt to escalate the crisis. The Euro-summit on December 9 will bring treaty changes that allow countries to exit the Euro. Everybody assumes this is to “punish” deficit offenders, when, in fact, it is Germany’s carefully crafted exit from the Euro-zone.

The remaining countries will be free to print their way out of looming insolvency, albeit at the price of having to figure out who will pay for the substantial losses on PIIGS bonds parked at the ECB.

Germany will see its currency gradually strengthen, and temporarily suffer from declining exports, but Germany has lived well with a strong currency before. The alternative, a complete melt-down of the Euro-zone, is definitely less appealing.