Some of my clients like to challenge my (admittedly gloomy) views, forcing me to think – which isn’t such a bad thing to do.

It started off with Cam Hui’s “A Dalio explanation of Evans-Pritchard’s dilemma“. After laying down his strategy on winning the game of Monopoly, Dalio goes on to model the economy onto the board game. So far so good.

Then, Dalio is quoted in a Barron’s interview, describing the current phase of the U.S. deleveraging experience as “beautiful”. He goes on to explain the three options for reducing debt: austerity, restructuring and printing money.

“A beautiful deleveraging balances the three options. In other words, there is a certain amount of austerity, there is a certain amount of debt restructuring, and there is a certain amount of printing of money. When done in the right mix, it isn’t dramatic. It doesn’t produce too much deflation or too much depression. There is slow growth, but it is positive slow growth. At the same time, ratios of debt-to-incomes go down. That’s a beautiful deleveraging.”

That sounds pretty good and makes sense. Or does it?

- I think Mr. Dalio would not be too upset if we labeled him a “Keynesian” (believing the government has to step in where private sector spending falls short).

- You could respond that it was Keynesian policies which brought us to the current situation in the first place (to which Keynesians will respond that their policies did not work out because there was not enough spending. Which is like saying “the kid is not behaving because you didn’t hit it hard enough“).

- Furthermore, how is the government sector on a different “planet” than the household sector? In the end, isn’t government debt (and hence fiscal deficits) supported and borne by taxpayers (read: household sector)? No sovereign entity in the world would be able to issue debt unless backed by taxpayers (or, for that matter, gold).

- As governments incur additional debt it is actually taxpayers’ future income that is on the block (as tax rates will have to go up to pay for additional debt service burden). Leverage is simply being shifted around. Oh, and for that time-shift argument (“tax receipts will have increased by the time the debt comes due”) – I believe it when I see it. There has been not a single country which has paid back its debt incurred under the fiat money system.

- If the future rate of inflation is below the interest rate paid on additional government debt, the net present value of deficit spending is negative (we are neglecting the argument over whether government can spend efficiently or not).

- Interest rates at issuance are fixed (exception: floaters). The decision whether to run fiscal deficits boils down to the following question: will future inflation exceed the interest paid (in order to devalue debt faster than accrued interest)?

- This makes the success of Keynesian policies dependent on elevated inflation. Governments are motivated, in a perverse way, to work towards reducing the value of money.

- This is in contradiction of central bankers’ (presumed) goal of preserving the function of money as a store of value, setting them up for a clash with governments (assuming they are not in cahoots anyways).

- However, there is no known case of a government successfully printing its way out of excessive debt (while there are plenty of examples for the opposite).

- It’s a loose-loose-situation: Should the government succeed in creating inflation, (1) financially prudent savers are punished, (2) low-income families are hurt (as they have no means to invest in assets benefiting from inflation) and (3) debt service costs are likely to increase as existing debt matures and needs to be rolled over.

- Should the government not succeed in creating inflation, future consumption will be burdened by additional taxes, lowering future growth and making excessive debt unsustainable.

- Will printing money “compensate” for money destroyed by debt write-offs? Turned the other way ’round, was money ever “un-printed” to compensate for money created from fractional banking and/or increased levels of debt?

- Cullen Roche of Pragmatic Capitalism states “QE [quantitative easing] doesn’t do much – it’s the great monetary non-event” (“Why QE is not working”).

- In the comments section of above article Cullen points out that

“It is flawed economic thinking to target nominal wealth. Stock prices are not real wealth until realized gains are taken. More importantly, stocks are based on the underlying value of the assets they represent. Pushing stock prices up does not make the companies more profitable. So hoping that people will spend more of their current income because of a false price appreciation in the market is a misguided policy.”

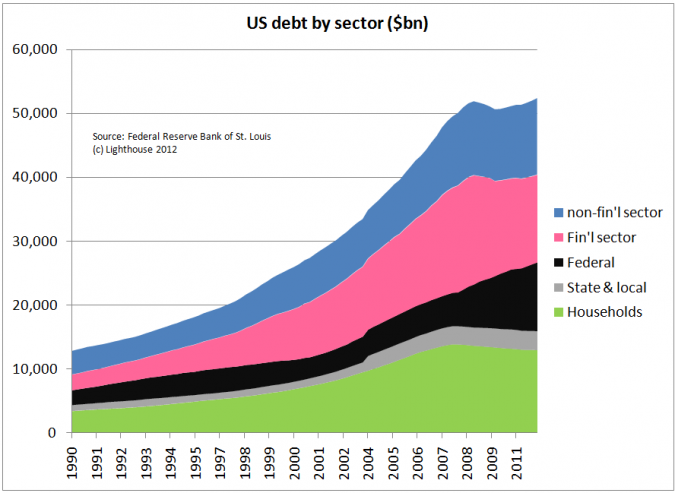

- So let’s take a look at Mr. Dalio’s “beautiful deleveraging”. Here’s US debt by sector:

Observations:

- Households are de-leveraging; so are financial corporations.

- This happens at the expense of the government sector, which continues to lever up.

- Total debt (government + households + corporations) is actually higher (by $800bn) than when the “beautiful deleveraging” began.

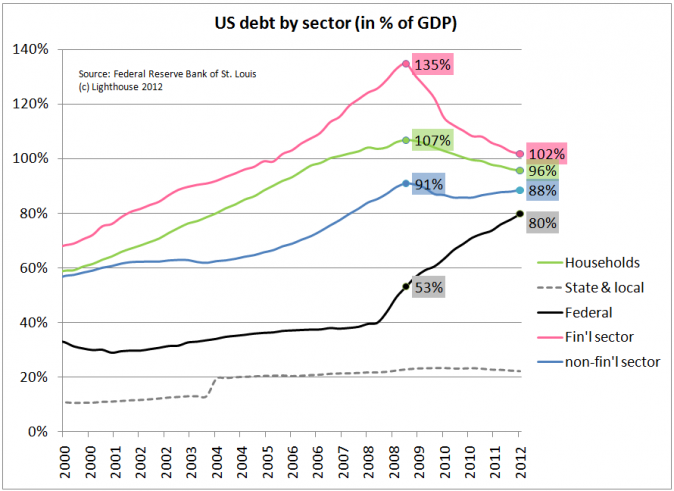

- Peak debt-to-GDP has been reached in Q1 2009 for households, financial and non-financial corporations.

- Since then (latest data Q1 2012), households have de-levered by 11%-points of GDP (or $654bn).

- Non-financial corporations reduced debt by 3%-points (or $406bn).

- Financial corporations, however, de-levered by a stunning 33%-points (or $3,375bn).

- The flip-side of this: Federal debt-to-GDP increased by 27%-points (or $4,030bn).

- While the household sector has done “it’s thing” it usually does during recessions (de-lever), it become clear who the main beneficiary of additional government debt is: the financial sector.

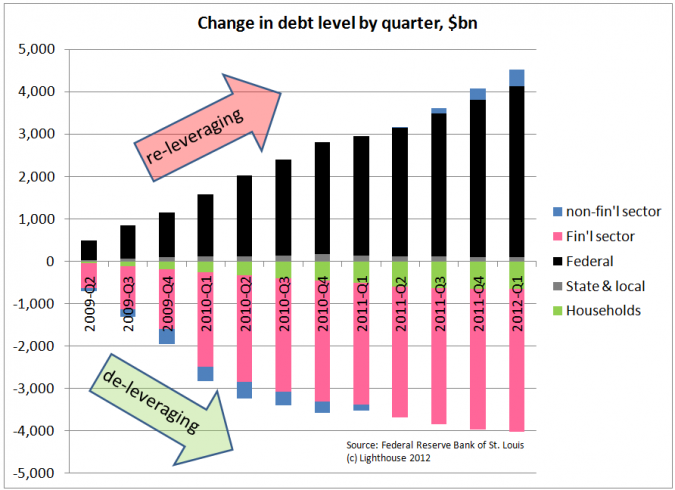

Looking at quarterly changes in sector debt visualizes it nicely:

- Mr. Dalio and his firm (Bridgewater Associates, the world’s biggest hedge fund) are part of this financial sector. No wonder he describes this kind of deleveraging as “beautiful”.

- Mr. Dalio, who, according to a recent Bloomberg story (Connecticut offers millions to aid Bridgewater expansion), “was paid $3.9bn in 2011” is taking all kinds of tax breaks / “forgivable loans” to be lured to move from Connecticut to… Connecticut (at least UBS and RBS moved to the state when receiving tax breaks).

- I have walked through the waterfront area of Stamford. A lot of low-income families, often minorities, living in simple homes. The city is building new, expensive apartments for the new, well-paid arrivals, gentrifying the area.

- From Bloomberg:

“If the region [Fairfield county] were a country, it would be the world’s 12th-most unequal in terms of income, ranking just below Guatemala.”

- As for debt write-downs, this Zerohedge post speaks for itself: Deleveraging needed in next 4 years: $28 trillion

CONCLUSION:

While Mr. Dalio’s narrative reads well, it doesn’t stand up to common sense. Unfortunately there is lingering suspicion his views on government spending are a mere ploy to advocate fore transferring even more debt from “his” sector onto taxpayers, while at the same time transferring taxpayers’ money to his firm via tax breaks.